The Munkacs Hebrew Gymnasium was among the most progressive experiments in the history of Jewish secondary education.

Bob Bahr – September 18, 2019

It was one of the most progressive experiments in the history of Jewish secondary education in Eastern Europe. The Munkacs Hebrew Gymnasium, in a major Jewish community in the Carpathian Mountains, was established in 1925 as a school where every subject in a modern high school curriculum was taught in Hebrew. Young Jewish men and women studied alongside one another as equals. Historians have described it as the most prestigious Jewish high school east of Warsaw.

One of the last graduates of that esteemed institutions was Eugen Schoenfeld of Atlanta, who died earlier this year at the age of 93. He was a retired professor of sociology and a former chair of the sociology department at Georgia State University. We were close friends in the last decade of his life and he often spoke of his school years in Munkacs as among the most important in his life.

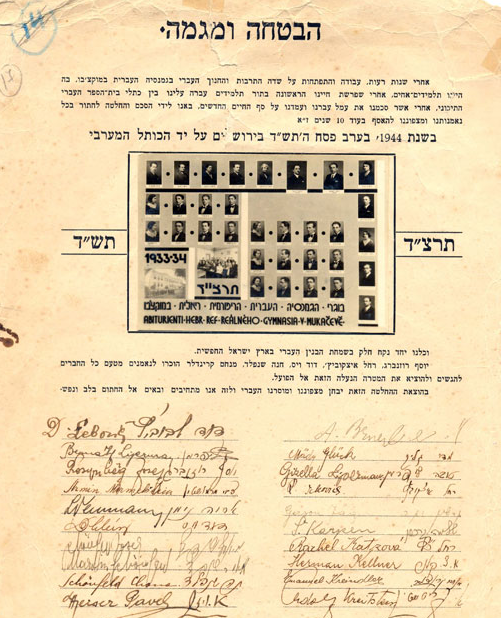

The school was taught by a staff which had a deep commitment to Zionism. Some were fortunate enough to flee the city in the years leading up to World War II. A 1934 document in the archives of the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum signed by 20 graduates of the class of 1934 promises that they will all meet 10 years later, on the eve of Passover, by the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

Ten of the signatories were still alive in 1944 for that fateful meeting. The founder of the school, Dr. Chaim Kugel, made his way to Jerusalem as well, and eventually served as mayor of the city of Holon in the modern State of Israel.

Dr. Schoenfeld’s father was a bookseller in Munkacs, and although he was an observant, Orthodox Jew, he, and all the other parents who sent their children to the Gymnasium, were excommunicated. It was done by the most important religious figure in Munkacs, the Munkaczer Rebbe Chaim Elazar Shapira. For 24 years he ruled his community with an iron fist.

When the cornerstone for the new school was being laid in 1925, the rebbe gathered his followers in the Great Synagogue and by the light of black candles, symbolically banished all the teachers and staff of the Gymnasium along with any parent who sent their children there.

The rebbe had established a large yeshiva to rival the secular school and he admonished his religious family to shun their co-religionists. He was an ardent anti-Zionist and in a 1934 newsreel film, can be seen wagging his finger in opposition to immigration, particularly to America.

But the same newsreel, shot by a visiting Soviet camera crew, showed the young men and women of the Gymnasium dancing a spirited Israeli horah. Also seen in the newsreel of the time is a 9-year-old Schoenfeld, singing the “Hatikvah,” the Zionist anthem, with his secular elementary school classmates.

Life in Munkacs, where Schoenfeld grew up, became increasingly difficult for Jews after the Munich conference in 1938. Munkacs became a part of Hungary, which allied itself with Nazi Germany, and the economic noose around Jews tightened.

While Jews in Paris, Amsterdam, Vilna, and Vienna were being transported to their deaths in the concentration camps, Schoenfeld and his fellow students continued their studies at the Gymnasium. Hungary’s alliance with Nazi Germany postponed, for a time, the Final Solution.

Schoenfeld graduated in the spring of 1943, after passing his final written and oral exams in Hebrew, the last graduating class before the German invasion of Hungary in April of 1944. By May 30, the German commandant of Munkacs could certify that the city was Judenrein, all 15,000 Jews had been shipped off to Auschwitz. The gymnasium became a German military hospital.

Schoenfeld and his father, the bookseller, were among the 2,000 that survived, but his mother, his brother, sister and so many of his classmates, friends and family were murdered.

The great educational experiment in Munkacs, like so much that was so glorious about Jewish life in pre-Holocaust Europe, had died as well.