The epidemic that brought Jews back to Jerusalem

Fleeing a Galilean plague, a handful of the Vilna Gaon’s students rewrote the holy city’s history

By ZACK ROTHBART MAY 21, 2020

The ‘Vilna Gaon Map’ is believed to be a copy of a map drawn by the Gaon, which was illustrated by his students shortly after his death around 1800.

(photo credit: ERAN LAOR CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION/NATIONAL LIBRARY OF ISRAEL)

A century ago, the Spanish Plague killed tens of millions of people globally.

A century before that, communities throughout the eastern Mediterranean were devastated by a bubonic plague outbreak, which reached the ancient Galilean city of Safed in 1812, quickly decimating its population.

Just a few years prior, three waves totaling some five hundred followers of the Vilna Gaon – one of Jewish history’s intellectual and spiritual giants – had come to the Land of Israel from White Russia, fulfilling their leader’s own dream a decade after his death. It was a significant demographic boost to the relatively small and overwhelmingly Sephardi Jewish community already in what was then Ottoman Palestine.

An illustration of the Vilna Gaon. From the Abraham Schwadron Portrait Collection, National Library of Israel archives

Nearly a full century before Herzl, some consider the arrival of the Vilna Gaon’s students to be a watershed event in the history of modern Zionism.

The failure of the last major group of Ashkenazi Jews that tried to establish itself in the Land of Israel was the main reason why this group had to settle for the slightly less holy city of Safed, instead of Jerusalem. At the end of the 1600s, a group led by Polish Jew “Judah the Pious” had established a community in Jerusalem. The community was soon unable to support itself, nor pay off its growing debts. Ashkenazi Jews were banned from living in the holy city. Those already there either moved out or lived in disguise, dressing like their Sephardic brethren. Not particularly interested in the differences between a Litvak and a Hassid or any other intra-religious distinctions for that matter, the local authorities held all Ashkenazim accountable for the debts owed.

Needless to say, a large group of Jews from White Russia would not feel particularly welcome.

In fact, it would take the bubonic plague to get Ashkenazim back into Jerusalem.

With the plague ultimately claiming the lives of some 80% of Safed’s Jewish community, towards the end of 1815 some of the Vilna Gaon’s disciples decided it was time to finally go up to Zion.

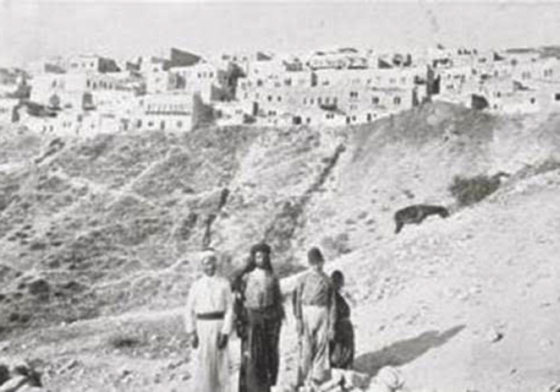

Safed in the 19th century. From the Lenkin Family Collection of Photography at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries

The group was led by Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Shklov, a man who had led efforts to organize and print the Vilna Gaon’s writings following his death in 1797, and who had also led the first wave of immigrants in 1808. Rabbi Yisrael of Shklov, the other leader of the community, would briefly flee to Jerusalem but ultimately choose to stay in Safed. Efforts were made to ensure that Rabbi Menachem Mendel’s group remained small in number and did not syphon off too much funding from the communities’ patrons throughout Europe, many of whom had been cultivated by Rabbi Yisrael as he made fundraising trips across the continent.

According to various legends, the Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem was so small that they did not have a minyan (traditional Jewish prayer quorum of ten adult males), and would either pay a Sephardi Jew to be their tenth man; utilize a legal loophole to count a child holding a Torah scroll as a member of their prayer quorum; or simply count the Torah scroll.

Nonetheless, Rabbi Menachem Mendel and his band were determined to reestablish an Ashkenazi presence in the holy city.

It took about five years, but after sending representatives all the way to Istanbul to negotiate with the Ottoman authorities, Rabbi Menachem Mendel’s men succeeded in securing a royal decree annulling the debts owed by the previous un-related Ashkenazi community, decades earlier. They then successfully focused their efforts on securing additional documents from local and international Islamic and civil authorities that would ultimately allow them to develop the compound which had been abandoned by the previous Ashkenazi community and destroyed by its creditors. Warm relations with some of the Christian and Muslim neighbors certainly did not hurt these efforts.

Letter from R. Yisrael of Shklov asking an emissary to speed up efforts to obtain Turkish approval for rebuilding Jerusalem’s Hurva Synagogue, and not to hesitate to go to Vilna to collect donations for distribution to the community. From the National Library of Israel archives

Rabbi Menachem Mendel and his group thus succeeded in both ridding themselves of the debt left by a community to whom they had no connection, and then achieving official recognition as (in some way) the lawful heirs to the property rights of that very same community!

While visiting Jerusalem in 1837, Rabbi Yisrael of Shklov, the head of the Safed community, received word of a devastating earthquake in the Galilee. His entire city was destroyed, 4,000 members of its Jewish community lost. Perhaps he took it as a sign or else simply had no other options, but Rabbi Yisrael decided to stay in Jerusalem for the last two years of his life. Many refugees from Safed did the same, joining the followers of Rabbi Menachem Mendel and their descendants.

Ultimately, this small contingent of the Vilna Gaon’s disciples laid the foundation for much of the dramatic renewal and expansion of Jewish life in Jerusalem which continues until today.

Israeli President Reuven Rivlin is one of many notable descendants of these early Zionists. A mysterious and controversial work entitled “Kol HaTor” (“The Voice of the Turtledove”) was purportedly passed down in the Rivlin family for generations before being published in the 20th century. It includes Kabbalistic teachings attributed to the Vilna Gaon and relating to the Messianic age. In the work, two dates on the Jewish calendar were identified as having exceptional spiritual qualities especially as related to the redemption of the Jewish people. The first was the Fifth of Iyyar, which we now celebrate as Israeli Independence Day. The second was the 27th of Iyyar, the date on which – at the height of the Battle for Jerusalem in 1967 – the decision was made to unify the city under Jewish sovereignty for the first time in two millennia.

Israeli soldiers overlook the newly liberated Western Wall and the Old City of Jerusalem in June 1967 (Photo: Dan Hadani). From the Dan Hadani Archive, part of the Pritzker Family National Photography Collection at the National Library of Israel

This article has been published as part of Gesher L’Europa, the National Library of Israel’s initiative to connect with people, institutions and communities in Europe and beyond.

Thanks to Dr. Zvi Leshem, director of the National Library of Israel’s Gershom Scholem Collection for Kabbalah and Hasidism for his insightful comments.