The opinions expressed on this webpage represent those of the individual authors and, unless clearly labeled as such, do not represent the opinions or policies of TBS

What did Jesus really look like?

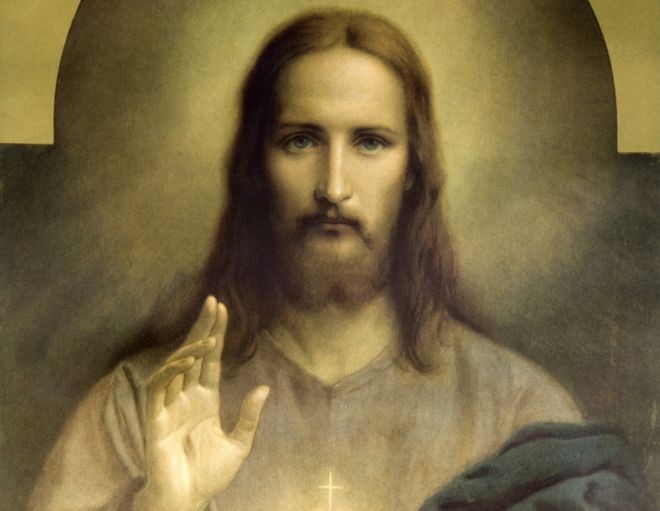

Everyone knows what Jesus looks like. He is the most painted figure in all of Western art, recognised everywhere as having long hair and a beard, a long robe with long sleeves (often white) and a mantle (often blue).

Jesus is so familiar that he can be recognised on pancakes or pieces of toast.

But did he really look like this?

Probably not.

In fact this familiar image of Jesus actually comes from the Byzantine era, from the 4th Century onwards, and Byzantine representations of Jesus were symbolic – they were all about meaning, not historical accuracy.

They were based on the image of an enthroned emperor, as we see in the altar mosaic of the Santa Pudenziana church in Rome.

Jesus is dressed in a gold toga. He is the heavenly ruler of all the world, familiar from the famous statue of long-haired and bearded Olympian Zeus on a throne – a statue so well-known that the Roman Emperor Augustus had a copy of himself made in the same style (without the godly long hair and beard).

Byzantine artists, looking to show Christ’s heavenly rule as cosmic King, invented him as a younger version of Zeus. What has happened over time is that this visualisation of heavenly Christ – today sometimes remade along hippie lines – has become our standard model of the early Jesus.

So what did Jesus really look like?

Let’s go from head to toe.

1. Hair and beard

When early Christians were not showing Christ as heavenly ruler, they showed Jesus as an actual man like any other: beardless and short-haired.

But perhaps, as a kind of wandering sage, Jesus would have had a beard, for the simple reason that he did not go to barbers.

General scruffiness and a beard were thought to differentiate a philosopher (who was thinking of higher things) from everyone else. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus considered it “appropriate according to Nature”.

Otherwise, in the 1st Century Graeco-Roman world, being clean-shaven and short-haired was considered absolutely essential. A great mane of luxuriant hair and a beard was a godly feature, not replicated in male fashion. Even a philosopher kept his hair fairly short.

A beard was not distinctive of being a Jew in antiquity. In fact, one of the problems for oppressors of Jews at different times was identifying them when they looked like everyone else (a point made in the book of Maccabees). However, images of Jewish men on Judaea Capta coins, issued by Rome after the capture of Jerusalem in 70AD, indicate captive men who are bearded.

So Jesus, as a philosopher with the “natural” look, might well have had a short beard, like the men depicted on Judaea Capta coinage, but his hair was probably not very long.

If he had had even slightly long hair, we would expect some reaction. Jewish men who had unkempt beards and were slightly long-haired were immediately identifiable as men who had taken a Nazirite vow. This meant they would dedicate themselves to God for a period of time, not drink wine or cut their hair – and at the end of this period they would shave their heads in a special ceremony in the temple in Jerusalem (as described in Acts chapter 21, verse 24).

But Jesus did not keep a Nazirite vow, because he is often found drinking wine – his critics accuse him of drinking far, far too much of it (Matthew chapter 11, verse 19). If he had had long hair, and looked like a Nazirite, we would expect some comment on the discrepancy between how he appeared and what he was doing – the problem would be that he was drinking wine at all.

2. Clothing

At the time of Jesus, wealthy men donned long robes for special occasions, to show off their high status in public. In one of Jesus’s teachings, he says, “Beware of the scribes, who desire to walk in long robes (stolai), and to have salutations in the marketplaces, and have the most important seats in the synagogues and the places of honour at banquets” (Mark chapter 12, verses 38-39).

The sayings of Jesus are generally considered the more accurate parts of the Gospels, so from this we can assume that Jesus really did not wear such robes.

Overall a man in Jesus’s world would wear a knee-length tunic, a chiton, and a woman an ankle-length one, and if you swapped these around it was a statement. Thus, in the 2nd Century Acts of Paul and Thecla, when Thecla, a woman, dons a short (male) tunic it is a bit of a shock. These tunics would often have coloured bands running from the shoulder to the hem and could be woven as one piece.

On top of the tunic you would wear a mantle, a himation, and we know that Jesus wore one of these because this is what a woman touched when she wanted to be healed by him (see, for example, Mark chapter 5, verse 27). A mantle was a large piece of woollen material, though it was not very thick and for warmth you would want to wear two.

A himation, which could be worn in various ways, like a wrap, would hang down past the knees and could completely cover the short tunic. (Certain ascetic philosophers even wore a large himation without the tunic, leaving their upper right torso bare, but that is another story.)

Power and prestige were indicated by the quality, size and colour of these mantles. Purple and certain types of blue indicated grandeur and esteem. These were royal colours because the dyes used to make them were very rare and expensive.

But colours could also indicate something else. The historian Josephus describes the Zealots (a Jewish group who wanted to push the Romans out of Judaea) as a bunch of murderous transvestites who donned “dyed mantles” – chlanidia – indicating that they were women’s wear. This suggests that real men, unless they were of the highest status, should wear undyed clothing.

Jesus did not wear white, however. This was distinctive, requiring bleaching or chalking, and in Judaea it was associated with a group called the Essenes – who followed a strict interpretation of Jewish law. The difference between Jesus’s clothing and bright, white clothing, is described in Mark chapter 9, when three apostles accompany Jesus to a mountain to pray and he begins to radiate light. Mark recounts that Jesus’s himatia (in the plural the word may mean “clothing” or “clothes” rather than specifically “mantles”) began “glistening, intensely white, as no fuller on earth could bleach them”. Before his transfiguration, therefore, Jesus is presented by Mark as an ordinary man, wearing ordinary clothes, in this case undyed wool, the material you would send to a fuller.

We are told more about Jesus’s clothing during his execution, when the Roman soldiers divide his himatia (in this case the word probably refers to two mantles) into four shares (see John chapter 19, verse 23). One of these was probably a tallith, or Jewish prayer shawl. This mantle with tassels (tzitzith) is specifically referred to by Jesus in Matthew chapter 23, verse 5. This was a lightweight himation, traditionally made of undyed creamy-coloured woollen material, and it probably had some kind of an indigo stripe or threading.

3. Feet

On his feet, Jesus would have worn sandals. Everyone wore sandals. In the desert caves close to the Dead Sea and Masada, sandals from the time of Jesus have come to light, so we can see exactly what they were like. They were very simple, with the soles made of thick pieces of leather sewn together, and the upper parts made of straps of leather going through the toes.

4. Features

And what about Jesus’s facial features? They were Jewish. That Jesus was a Jew (or Judaean) is certain in that it is found repeated in diverse literature, including in the letters of Paul. And, as the Letter to the Hebrews states: “It is clear that our Lord was descended from Judah.” So how do we imagine a Jew at this time, a man “about 30 years of age when he began,” according to Luke chapter 3?

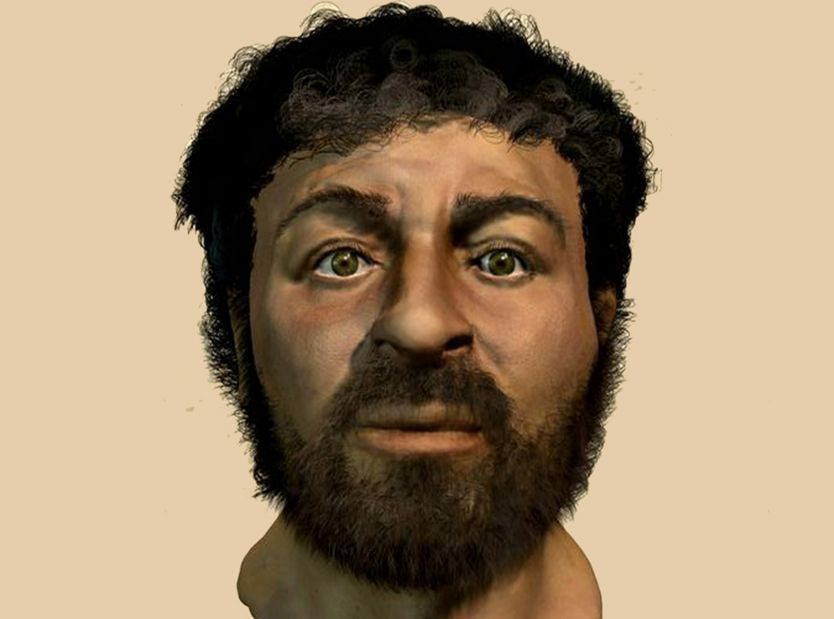

In 2001 forensic anthropologist Richard Neave created a model of a Galilean man for a BBC documentary, Son of God, working on the basis of an actual skull found in the region. He did not claim it was Jesus’s face. It was simply meant to prompt people to consider Jesus as being a man of his time and place, since we are never told he looked distinctive.

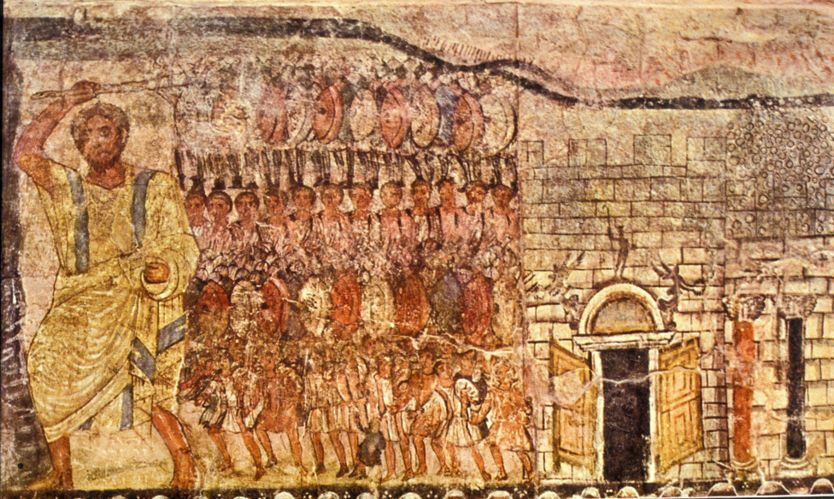

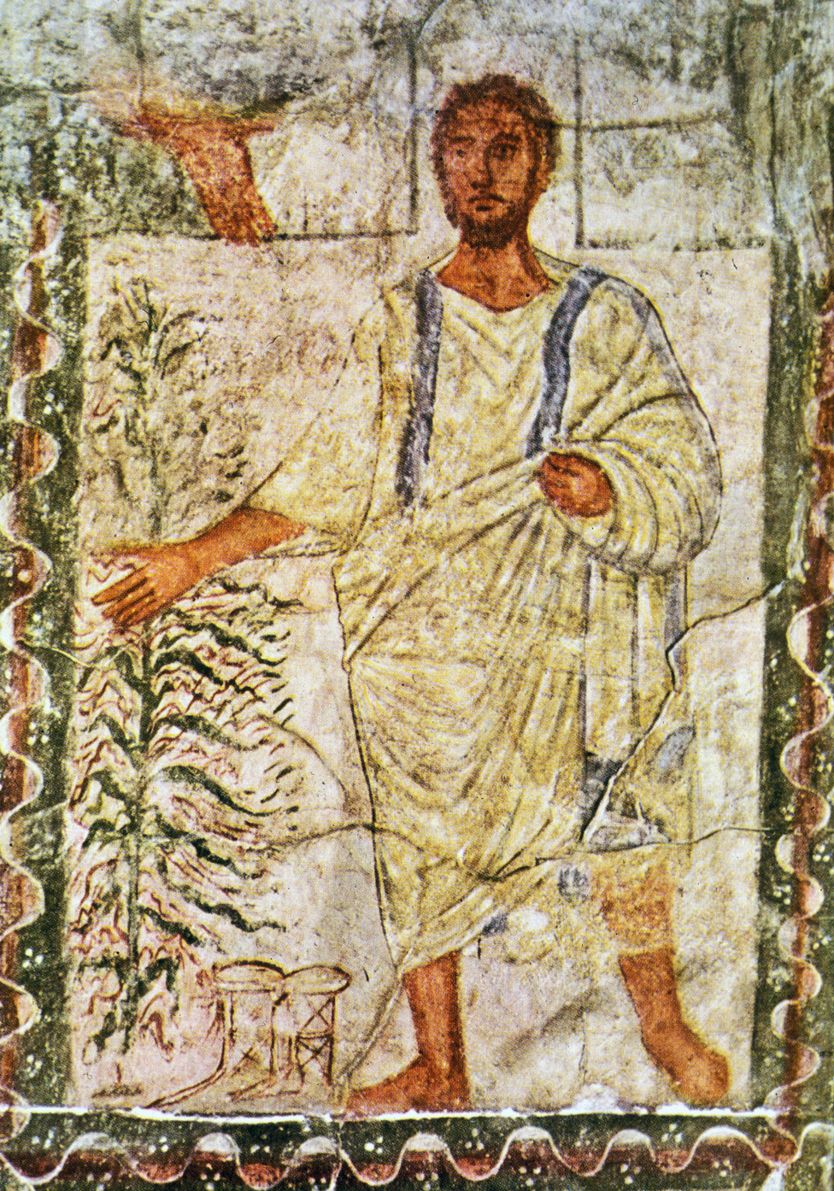

For all that may be done with modelling on ancient bones, I think the closest correspondence to what Jesus really looked like is found in the depiction of Moses on the walls of the 3rd Century synagogue of Dura-Europos, since it shows how a Jewish sage was imagined in the Graeco-Roman world. Moses is imagined in undyed clothing, and in fact his one mantle is a tallith, since in the Dura image of Moses parting the Red Sea one can see tassels (tzitzith) at the corners. At any rate, this image is far more correct as a basis for imagining the historical Jesus than the adaptations of the Byzantine Jesus that have become standard: he’s short-haired and with a slight beard, and he’s wearing a short tunic, with short sleeves, and a himation.

Joan Taylor is professor of Christian Origins and Second Temple Judaism at King’s College London and the author of The Essenes, the Scrolls and the Dead Sea.