The opinions expressed on this webpage represent those of the individual authors and, unless clearly labeled as such, do not represent the opinions or policies of TBS.

The stolen missile boats Israel used in the Yom Kippur War

Half a century has passed since Israel defied a French embargo and stole its own boats from Cherbourg harbor on Christmas Eve, titillating the world media.

The vessels would be refueled at sea by Israeli merchant ships moving into position along the 5,600-km. escape route.

As television crews flew over the Mediterranean searching for the boats, and the French defense minister called for the air force to “interdict” the fleeing vessels, the world media chortled at Israel’s chutzpah. But the real story was far bigger than they knew.

It had begun in 1961 when the commander of the Israel Navy, V.-Adm. Yohai Bin-Nun, summoned senior staff to a brainstorming session in navy headquarters on Haifa’s Mount Carmel. He passed on warnings that the navy might be downgraded to a coast guard if its antiquated fleet of World War II hand-me-downs could no longer defend Israel’s sea lanes. The task would then be left to the air force. What options did the navy have to stay relevant? Bin-Nun asked his staff.

From the two-day meeting, an unusual proposal floated to the surface. Israel’s fledgling military industries had developed a crude missile which was rejected by both the Artillery Corps and air force. If mounted on small boats, an officer at the meeting suggested, it could give them the punch of heavy cruisers.

Small meant affordable. It also meant much smaller crews; the sinking of a destroyer with a crew of 200-250 men, then the navy’s backbone, would be catastrophic for a small country like Israel. Small boats could not take heavy guns because of the recoil, but missiles have no recoil.

The idea was dismissed by most of those present, who noted that there was not a Western country that had such boats. However, the proposal resonated with Bin-Nun. It might be fanciful, but he had heard no better idea. After mulling it over a few months, he asked his deputy, Capt. Shlomo Erell, to examine the proposal seriously.

Deputy defense minister Shimon Peres, to whom Bin-Nun had gone for funding, gave the project his blessing. Bin-Nun said that if he got just six missile boats, he would scrap the rest of the fleet.

TWO YEARS before, Peres had traveled to snow-covered Bavaria for a secret five-hour meeting in the home of German defense minister Franz-Josef Strauss. At the center of their talk was the relationship between the Jewish state and the country that had murdered six million Jews less than two decades before. The emotional chasm that lay between their countries was as yet unbridged by diplomatic ties.

Peres suggested that Germany take a significant step toward acknowledging its past by furnishing Israel with arms needed for its survival, doing so without publicity, to avoid Arab ire, and without payment, because Israel couldn’t afford it.

Strauss said he would recommend the proposal to his government. German chancellor Konrad Adenauer confirmed that pledge to David Ben-Gurion, when the two elder statesmen met in New York.

The next budget of the German Federal Republic would contain an allocation of $60 million for “aid in the form of equipment” over a five-year period, without specifying the recipient. A list of military equipment had been drawn up, most of it standard items like artillery and half-tracks. After his conversation with Bin-Nun, Peres had the list adjusted to include six missile boats. (Six more would be added later.)

Erell, who succeeded Bin-Nun as navy chief, formed a think tank with personnel from the navy and from Israel Aircraft Industries to explore the concept in detail. The project was given the lyrical code name of Shalechet (Falling Leaves). A maverick engineer, Ori Even-Tov, was lured from Rafael, Israel’s leading defense company, and succeeded in developing an effective sea-to-sea missile, the Gabriel, which would be at the heart of the entire program.

But Erell wanted a multipurpose vessel, not just a missile platform. In a meeting at the German Defense Ministry he said that, for Israel, the boats were capital ships that must be capable of carrying out an assortment of missions. It would have rapid-firing guns that could be used against planes, ships or shore targets, sonar for sub hunting, plus radar and communication equipment more advanced than those carried by destroyers several times its size.

The Shalechet team was rapidly expanded, obliging the navy to triple the number of men passing through its officers’ course. At the height of the decade-long project, hundreds of engineers, naval architects and others worked on the project every day of the year except Yom Kippur, often 12 to 14 hours a day; a few worked on Yom Kippur as well.

The project was shifted to a modern, windowless plant. Sometimes personnel who arrived early in the morning were startled when they left the building to see that night had come; even come and gone. There was no precedent for what they were doing and no textbook. The team members were working at the cutting edge of naval technology, forging solution after innovative solution, a precursor to Israel’s emergence as the Start-Up Nation. For many, it would be the high point of their lives.

Straw boss for the team developing the boats’ weapon system was Aviah Shalif, an engineer who had grown up in Jerusalem with Bin-Nun and Even-Tov. Wiry and acerbic, he would swiftly lay tangled problems bare and propose solutions. His ability to keep things moving forward mattered more than the relative merits of the technical approaches among which he had to choose. In a document of several hundred pages, Shalif formulated the “logic” of the weapon system, showing how all elements affected one another. It was done without the aid of a computer, which he had not yet learned to use.

Midway, Israel learned that the Soviet Union had beaten them to the punch. It had developed its own missile boats and was supplying dozens to Egypt and Syria. The boats were armed with the Styx missile, whose deadliness was demonstrated shortly after the Six Day War when a small Egyptian vessel, barely visible on the horizon, fired four missiles at the Israeli flagship, the destroyer Eilat. All hit, and the Eilat went down, the first vessel ever sunk by a ship-to-ship missile. Of the 200-man crew, 47 were killed and 100 wounded. The Styx threat loomed even larger when intelligence learned that it had twice the range of Israel’s Gabriel. The Arab boats could simply stay out of Gabriel range and unleash their no-miss missile in safety.

Erell asked the navy’s chief electronics officer, Capt. Herut Tzemah, if there was anything that could be done. Guessing at the electronic parameters of the Styx radar, Tzemah devised electronic countermeasures to divert incoming missiles. He also recommended as a backup rockets firing chaff – strips of aluminum that confuse radar. The efficacy of this anti-Styx umbrella could be tested only in combat. If he had guessed wrong, the war at sea would end quickly.

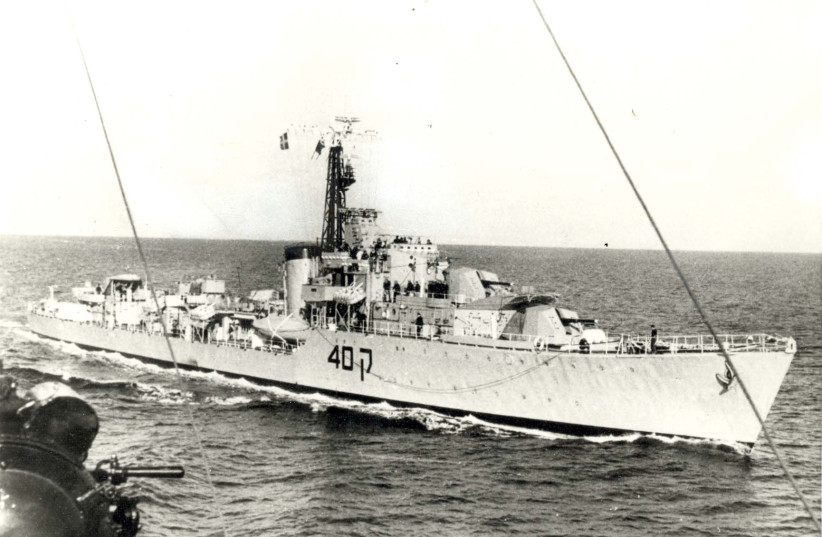

With the funds provided by Germany, 12 “patrol boats” were ordered from a Cherbourg shipyard. The vessels were modified versions of Germany’s sturdy Jaguar torpedo boat, itself a descendant of the E-boats (Schnellboot) that harried allied shipping in the North Sea in the Second World War. The vessels were to serve as platforms for the missile boat taking shape in the minds of the navy command.

Seven of the Cherbourg boats were launched – one every two or three months – and sailed for Israel, before French president Charles de Gaulle ordered an embargo following an Israeli commando raid on Beirut Airport. The embargo forbade taking the remaining boats to Israel, but their construction and even their testing at sea were permitted since the shipbuilder would receive final payment only when all the boats were completed.

ENTER V.-ADM. Mordecai (Mocca) Limon. He had been appointed commander of the Israel Navy at age 26 and was now head of Israel’s military purchasing mission in Paris. He was determined to get the remaining boats to Israel as soon as the last one was launched. In the next war, the navy would probably have to fight simultaneously on both the Egyptian and Syrian fronts and needed every boat it had.

Prime minister Golda Meir objected to Limon’s proposal to simply run off with the boats one night, saying that France would likely sever relations. Limon kept pushing, and she tempered the veto by saying that nothing “illegal” should be done that could endanger diplomatic ties. To Limon, the difference between legal and illegal could be no wider than a lawyer’s comma, and in the circumstances that might be wide enough to squeeze a missile-boat squadron through.

As the last boat neared completion toward the end of 1969, he arranged to meet for lunch in Copenhagen Airport with a Norwegian shipyard owner, Martin Siemm – a resistance hero in the war – who had visited Israel and had friends there. It was a friend who gave Limon Siemm’s name. Explaining the situation in Cherbourg, Limon asked if he would agree to help Israel out of its quandary. There would be no payment, only possible embarrassment or worse if the plot unraveled.

Siemm’s face brightened as he grasped the stakes involved and the ploy being spelled out. “Give me 48 hours,” he said. When he called Limon from Oslo it was to give his assent.

Meanwhile, the boats were being prepared for the breakout. Limon proposed that the boats depart on Christmas Eve, when security would be minimal. Supply officers avoided making suspicious bulk purchases for the trip by buying food in small quantities in numerous groceries and butcher shops around the greater Cherbourg area. Fuel was added to the boats in small increments almost daily so that, as they got lower in the water, it was difficult to perceive the change.

Concurrently, the legal obfuscation was proceeding apace. Siemm sent a letter to the owner of the Cherbourg shipyard, 75-year-old Felix Amiot, expressing interest in acquiring four to six fast boats for assistance in offshore oil exploration. Did Amiot have such craft at hand? The characteristics of the vessels he was seeking happened to match those of the Cherbourg boats. Amiot replied promptly that he had five suitable boats whose owners were “having trouble taking delivery.” Both letters had been drafted by Limon.

Amiot sent copies to Gen. Louis Bonte, the French official who would have to approve their sale. Bonte was delighted at the prospect of getting rid of the embarrassing clutter of five embargoed vessels in Cherbourg Harbor – bad for France’s image as a reliable arms exporter. He called Limon to inform him of the Norwegian offer and ask if Israel was prepared to waive its claim to the boats and accept its money back.

“Those are our boats,” replied Limon. “We paid for them and we need them.” However, he said, he would pass on Bonte’s query to the Defense Ministry in Tel Aviv. Limon had deftly inserted the sting.

Several days later, an anxious Bonte called to ask if he had received a reply yet. “Not yet,” said Limon. “I’ll call you when I do.”

He let a few more days pass before calling Bonte. “They went against my advice and are letting the boats go. They’re just fed up with the whole business.” France’s Interministerial Committee on Arms Exports duly gave the sale to Norway final approval.

On December 22, the three principal actors in the affair – Limon, Siemm and Amiot – met in Paris to sign two contracts which would be sent to Bonte’s office – one canceling the original contract by which Israel had purchased the boats from Amiot, the other a contract between Amiot and Siemm transferring the five boats to Oslo for the price Israel had paid.

The coup came the following day. The three men met again and signed a new set of agreements undoing everything they had signed the day before, returning the situation to the status quo ante. The boats were legally back in Israeli hands even though they had ostensibly been sold to a Norwegian company. These documents were not sent to Bonte; they were intended only to ensure the three parties would have no future claim on each other regarding the fictitious sale to Norway.

The breakout planning, which had been run out of Mocca Limon’s hip pocket, had by now become a quasi-military operation run from naval headquarters. Israeli merchant ships making regular runs to and from Europe were told by naval headquarters to deploy at given locations and times along the 5,600-km. escape route from Cherbourg to Haifa in order to fuel the small craft on their weeklong voyage or otherwise render assistance. Temporary fueling installations were built on two of the vessels, and their crews trained in fueling small craft at sea – not as easy as it looked.

There was even a brief language course to enable the Cherbourg boat crewmen – young draftees who may or may not be able to speak English – to communicate with the civilian seamen on the mother ships, a mix of Israelis and foreigners who used English between them. The course covered Hebrew-English nautical equivalents.

Radio wavelengths permitting the Cherbourg boats to communicate with the freighters were issued.

A few days before Christmas, close to 100 Israeli naval crewmen in civilian clothing were flown to Paris and dispatched by train in small groups to Cherbourg, where they were hidden below decks until departure.

Commanding the breakout in Cherbourg was Capt. Hadar Kimche. He had fixed the Christmas Eve departure for 8 p.m. when the good citizens of Cherbourg would be sitting down en famille to their holiday dinner. However, a powerful storm was churning the English Channel beyond the breakwater, and even large freighters were not venturing out. The five captains gathered in Kimche’s boat, listening to weather reports from the BBC and other sources. With them was the shipyard official, Monsieur Corbinais, who had overseen the construction of the boats. Near midnight, he left briefly to attend midnight mass at a nearby 14th-century church. He softly added a prayer of his own to the liturgy: “May they reach safe harbor.”

Limon had also come to see the boats off. He urged Kimche to depart regardless of the weather. Otherwise, they might be stuck for days, with constant danger of discovery. Kimche, however, said they would not move until the wind shifted. It was too dangerous now to cross the Bay of Biscay. As commander of the boats, the decision was his, not Limon’s.

At 1:30 a.m. a radioman monitoring the BBC entered with the latest bulletin: the west wind was shifting to the northwest and diminishing in strength. Kimche said they would await the 2 a.m. broadcast for confirmation. It came. “We leave at 2:30,” Kimche said. “Synchronize your watches.” The captains then hurried to their boats tied alongside.

As the craft moved off in single file, Limon waited on the pier in the driving rain, his coat collar turned up, to see if the boats would be turning back. After half an hour he drove to Amiot’s nearby residence and knocked on the door. “C’est moi, Mocca.” Amiot, in a robe, ushered him in.

“I want to inform you,” said Limon, “that the boats have sailed.”

Amiot bowed his head and wept. Limon sensed the old man’s relief that his contract had been honored. Amiot poured cognac and the pair toasted each other and toasted the boats. Before turning to leave, Limon took out a billfold from his jacket pocket and handed Amiot a check for $5 million, the final payment. The last boats had now been delivered.

They arrived in Haifa on New Year’s Eve 1970 to sirens and large crowds. To the public, the Cherbourg boats, presumed to be ordinary naval craft, had accomplished their mission by reaching the Israeli port. But it would be nearly four years before their conversion to missile boats was completed, tactical doctrine formulated and crews trained in a new type of warfare.

THE FIRST time the entire missile boat flotilla engaged in maneuvers together was the first week in October 1973. The boats returned to their base the morning before Yom Kippur, a day before the war’s outbreak.

On the first night, four Israeli missile boats engaged three Syrian missile boats off the Syrian port of Latakia in the first-ever missile-to-missile battle at sea. The Syrians, as expected, fired first.

The Israeli sailors watched fireballs arcing into the sky and then descended straight at them. All knew that every Styx fired at an Israeli target until now had hit – the four that sank the Eilat and two that sank a small wooden fishing boat a year afterward. The crewmen’s lives hung now on Tzemah’s educated guess regarding the Styx. In the final seconds of their trajectory, the missiles succumbed to an unseen force tugging at them and plunged into the sea.

The Soviet-built boats in the Arab fleets had no such electronic defenses. The Israeli vessels off Latakia closed range and destroyed two of the Syrian missile boats with Gabriels as well as two other warships. The captain of the third Syrian missile boat, witnessing what happened to his comrades and with no missiles left, drove his boat onto the shore so that he and his crew could escape. In a reprise two nights later, three Egyptian missile boats were sunk near Alexandria.

Erell, who died last year, had been in Europe when the war broke out. He returned to Israel, joining the flotilla during one of its nighttime forays against the Syrian coast. He was captivated by the way the captains – one of whom was his son, Udi – coordinated their movements despite the wild weavings and seeming confusion of a night battle at 40 knots.

The Israeli boats raked Syrian ports with gunfire and dashed toward them, trying to draw Syrian warships out. The Syrians did not come out, but there was fire from coastal artillery and occasionally missiles fired from inside their harbors. The boats seemed to slalom between the plumes thrown up in the sea. Along the coast, oil tanks had been set aflame by gunfire.

From the direction of Tartus to the south, four balls of flame suddenly appeared in the sky, heading in his direction like planes in formation. Erell was petrified; but if the others on the bridge also were, they managed to hide it.

“They’re beginning to turn,” said a bridge officer. To Erell, it seemed as if the lights were still heading between his eyes. But the bridge officer, with two weeks of battle under his belt, could make out a slight shifting. Soon, Erell could see it, too.

From the fourth day, the Arab fleets did not venture out of harbor. No Israeli boat was hit in the 18-day war, and the shipping lanes to Haifa remained open for much needed supplies.

A country with little naval tradition, a limited industrial base and a population of only three million – half that of New York City at the time – had challenged the advanced weaponry of a superpower at sea and achieved total victory, introducing a new naval age.

As a traumatized Israel tried to grasp what had happened to its vaunted army and air force on Yom Kippur, the navy’s performance was little noted. It would be two years before the navy’s performance was mentioned in a public forum.

But the navies of the world had taken note. The United States, which had been deeply concerned by the sinking of the Eilat for what it might portend for them, sent a large naval team to debrief the Israelis. The examination included a computer analysis of the missile clashes. The US had invested astronomical sums in shipboard antimissile systems, whereas the Israelis had performed superbly with a system so seemingly simple that the Americans were amazed it had worked at all.

The American team included Adm. Julian Lake, one of the world’s foremost experts on electronic warfare. He had studied EW systems in more than a score of allied countries around the world. He would tell a reporter that the way the Israel Navy had analyzed the nature of the threat facing it and taken the necessary steps to solve the problem “stands out as the one clear example [in the development of modern weapon systems] where everything was done right.”

THE ISRAELI missile boats – outnumbered and outranged by the Arab missile boats – had swept clear the Eastern Mediterranean of enemy vessels, kept the sea lanes to Haifa open, prevented attacks on Israel’s vulnerable coast, sunk at least eight Arab warships, including six missile boats, wreaked havoc on oil tank farms along Syria’s coast and drawn Arab troops far from the main battlefield by threatening commando landings. All this without losing a man or a boat. (Two Israeli frogmen were killed in penetrating Port Said, and two crewmen on patrol boats were killed in clashes in the Red Sea.)

The missile boats successfully eluded all 54 Styx missiles fired at them, as well as many hundreds of shells fired by shore batteries during nightly raids. The development of the boats and the Gabriel missile would spur Israel into an era of hi-tech on which much of its future economy would rest.

The Cherbourg Project was a reaffirmation of a beleaguered nation’s most precious asset – national will. In conceiving and undertaking something so unorthodox and risky; in the dedication invested in the Shalechet development program; in the tough-mindedness with which the boats were snatched from Cherbourg and then deployed against the Styx, “Cherbourg” testified that Israel’s life force had not ebbed.

The writer is author of The Boats of Cherbourg, newly reissued as a paperback. He is also author of The Yom Kippur War and The Battle for Jerusalem.

The French react

Although the French government fumed at the boats’ escape, most of the French public applauded the Israelis for their audacity, according to French polls, and so did virtually all the French media. The embargo, they understood, had not been imposed because of any harm Israel had done to France, but because of president Charles de Gaulle’s political tilt toward the Arab world after his withdrawal from Algeria.

The only reprisal against Israel was to demand the recall of Limon. Many in Israel had expected that he would be declared persona non grata, which would have barred his subsequent reentry even as a tourist. A straightforward recall carried no such sanction.

After his return to Israel, Limon became the local representative of Baron Edmond de Rothschild of France, who had extensive business interests in Israel. Limon’s connection to the House of Rothschild would become more intimate when his daughter married into another branch of the family.

Limon put off a return to France for half a year but finally flew to Paris to attend a business meeting. With some apprehension, he approached the passport control officer at the airport who examined his passport for some time. The officer turned the pages, looked at it sideways and then looked up at the tall traveler.

“You are Admiral Limon?” he asked. Limon acknowledged his identity. The officer rose and reached over the glass partition.

“Congratulations,” he said, shaking Limon’s hand. – A.R.