The Holocaust: Who are the missing million?

By Raffi Berg – BBC News, Jerusalem

Giselle Cycowicz (born Friedman) remembers her father, Wolf, as a warm, kind and religious man. “He was a scholar,” she says, “he always had a book open, studying Talmud [compendium of Jewish law], but he was also a businessman and he looked after his family.”

Before the war, the Friedmans lived a happy, comfortable life in Khust, a Czechoslovak town with a large Jewish population on the fringes of Hungary. All that changed after 1939,

when pro-Nazi Hungarian troops, and later Nazi Germany, invaded, and all the town’s Jews were deported to Auschwitz.

Giselle last saw her father, “strong and healthy”, hours after the family arrived at the Birkenau section of the death camp. Wolf had been selected for a workforce but a fellow prisoner under orders would not let her go to him.

“That would have been my chance to maybe kiss him the last time,” Giselle, now 89, says, her voice cracking with emotion.

Giselle, her mother and a sister survived, somehow, five months in “the hell” of Auschwitz. She later learned that in October 1944 “a skeletal man” had passed by the women’s camp and relayed a message to anyone alive in there from Khust.

“Tell them just now 200 men were brought back from the coal mine. Tell them that tomorrow we won’t be here anymore.” The man was Wolf Friedman. He was gassed the next day.

Image source, AFP

Six million Jews were murdered by the Nazis and their accomplices during World War Two. In many cases entire towns’ Jewish populations were wiped out, with no survivors to bear witness – part of the Nazis’ plan for the total annihilation of European Jewry.

Since 1954, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, Yad Vashem (“A Memorial and a Name”), has been working to recover the names of all the victims, and to date has managed to identify some 4.7 million.

“Every name is very important to us,” says Dr Alexander Avram, director of Yad Vashem’s Hall of Names and the Central Database of Shoah [Holocaust] Victims’ Names.

“Every new name we can add to our database is a victory against the Nazis, against the intent of the Nazis to wipe out the Jewish people. Every new name is a small victory against oblivion.”

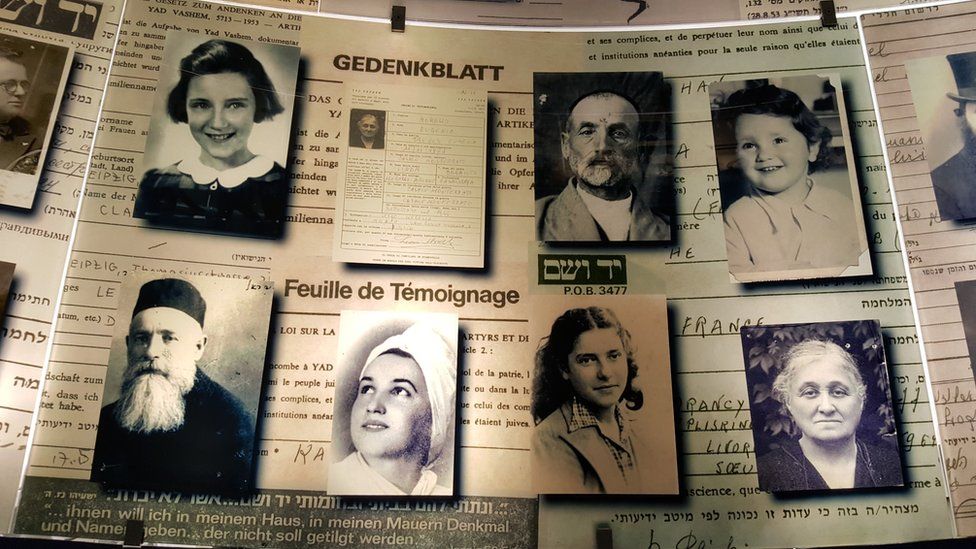

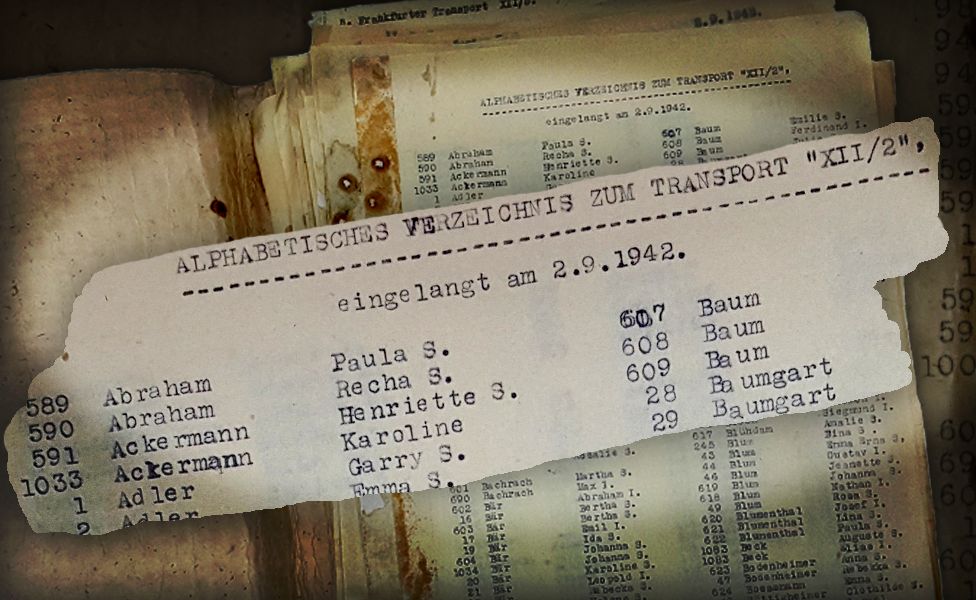

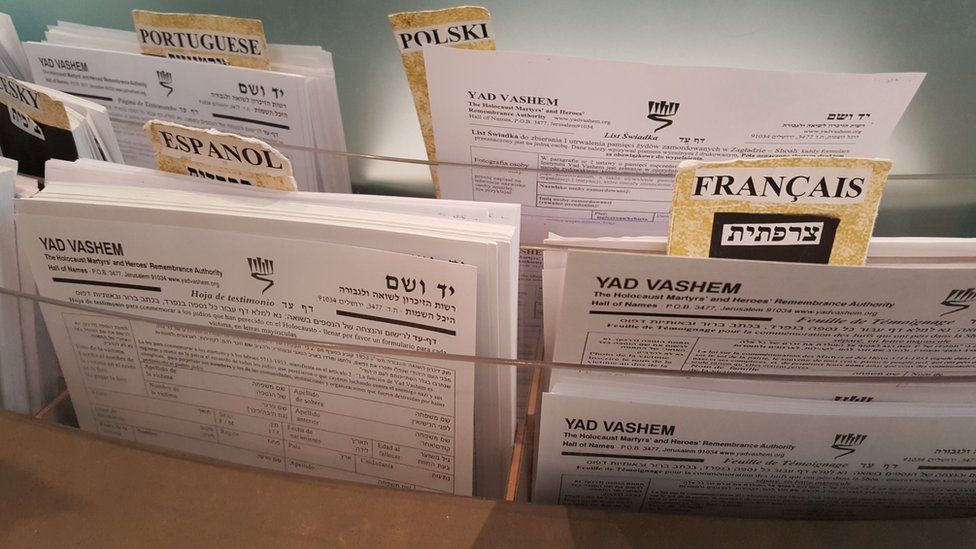

The institution, a sprawling complex of buildings, trees and gardens on the western slopes of Mount Herzl, gathers details about the victims in two ways: through information from those with knowledge of the deceased, and archive sources, ranging from Nazi deportation lists to Jewish school yearbooks.

Today Giselle has come to dedicate her father’s name, nearly 73 years after he was killed, a small piece in a vast jigsaw.

She is helped by trained staff through the process of recording Wolf’s details on a Page of Testimony, a one-page form for documenting biographical information about the deceased, such as where they lived before the War, their occupation and the members of their family, and, if available, a photograph.

“Only two-thirds of the way down do we ask where they were during the war and what happened to them,” Cynthia Wroclawski, deputy director of Yad Vashem’s Archives Division, points out.

“We’re interested in seeing a person as a person and who they were before they became a victim.”

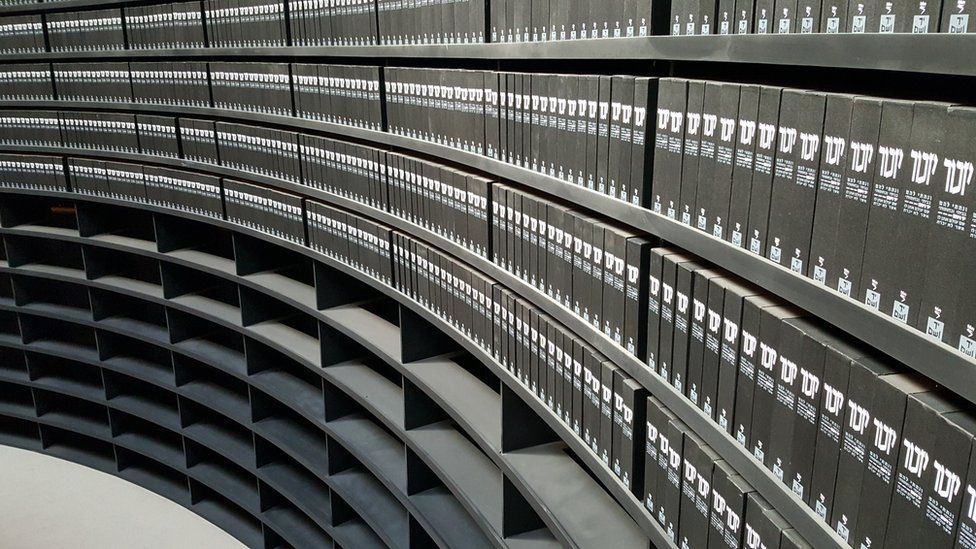

It is, the institution says, a kind of paper tombstone. So far Yad Vashem has collected 2.7m Pages of Testimony.

Each is stored in black boxes, each containing 300 pages – 9,000 boxes in all. They are kept in climate-controlled conditions on shelves surrounding a central installation, a 30ft-high conical lined with the faces of men, women and children who were murdered, rising up towards the sky.

Here in the Hall of Names groups of visitors pass through in quiet contemplation. There is space on the shelves for 11,000 more boxes – or 6m names in all.

With the last survivors dying out, Yad Vashem is facing a race against time to prevent more than a million unidentified victims disappearing without a trace.

This is apparent in the decreasing number of Pages of Testimony it receives – down from at least 2,000 per month five years ago to about 1,600 per month currently.

The memorial is trying to raise awareness, including among Holocaust survivors who have not yet come forward. For decades, for many of them the experience was still too painful to talk about.

“It’s quite a common occurrence, not only in Holocaust survivors but survivors of prolonged and extreme trauma in childhood,” says Dr Martin Auerbach, Clinical Director at Amcha, a support service in Jerusalem for Holocaust survivors.

That began to change, he says, after about 30 or 40 years, when many survivors started talking about what happened, not with their children but with their inquisitive grandchildren. Dr Auerbach sees the Names Recovery Project as a valuable part of the healing process.

“Filling out this page of information saying this was my father, mother, grandfather, nephews and nieces – you cannot bury your relatives who perished but you can remember them in a way that will commemorate them forever, so this is very important and also therapeutic for many survivors.”

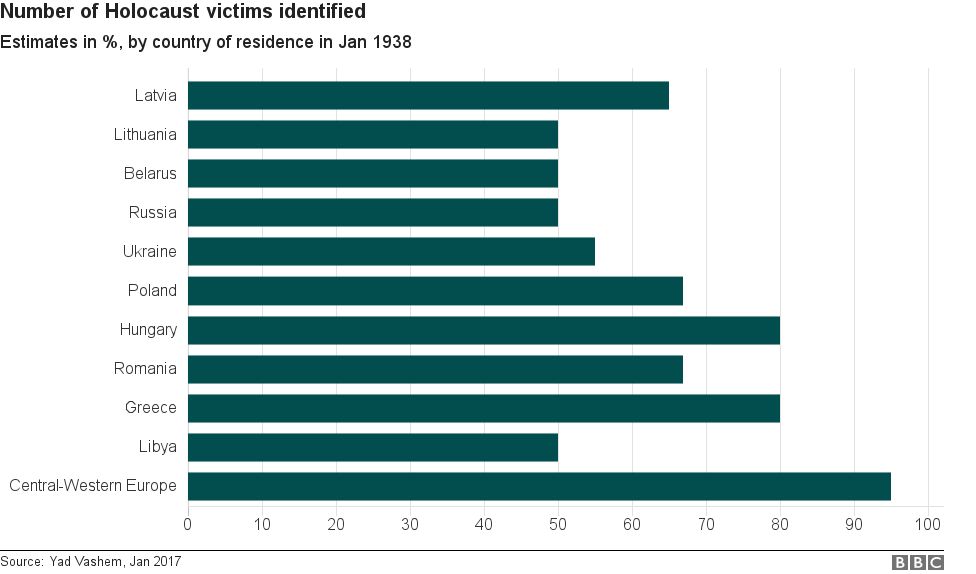

While Yad Vashem has made great strides in identifying victims from Western and Central Europe – about 95% have now been named – far fewer names have been uncovered in Nazi-occupied areas of Eastern Europe, where about 4.5m Jews were murdered.

This is because while there was an organised, official process of arrest and deportation further west, in the east whole communities were marched off and massacred without any such formalities.

Image source, AFP

An estimated 1.5m Jews alone were shot to death by the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing squads) in what has become known as the Holocaust by Bullets, after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.

In Babi Yar, in Ukraine, for instance, of the 33,000 Jews from Kiev and its surroundings who were slaughtered in a ravine in September 1941 in the largest massacre of its kind, about half are yet to be identified.

Others not murdered by the Einsatzgruppen died, without a trace, from starvation or exhaustion in ghettos and labour camps, or were killed in nearby extermination camps, where they had been herded without any kind of processing.

Yad Vashem is working with Jewish organisations in those countries to try to reach remaining survivors in the former Soviet Union, where the Holocaust was not officially commemorated, and who may have little awareness of the memorial’s existence.

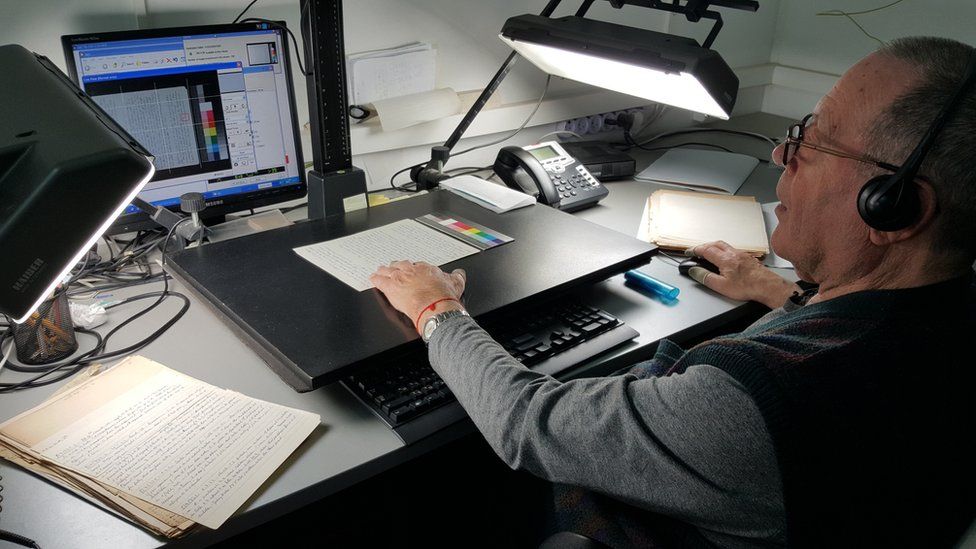

It is a massive and often complex task. The memorial holds some 205m Holocaust-related documents, which are examined meticulously in the search for names.

“There is a lot of documentation where there are names that are very scattered,” says Dr Avram. “Names mentioned in a letter here or a report there. This can be very labour intensive. Sometimes you have to go through thousands and thousands of pages just to retrieve a few dozen names.”

The difficulty is compounded by the fact that sources can be in 30-40 different languages, most are handwritten and can be in different scripts, such as Latin, Hebrew and Cyrillic. “Our staff not only need to be linguists but they need to know calligraphy,” says Dr Avram, himself a language expert.

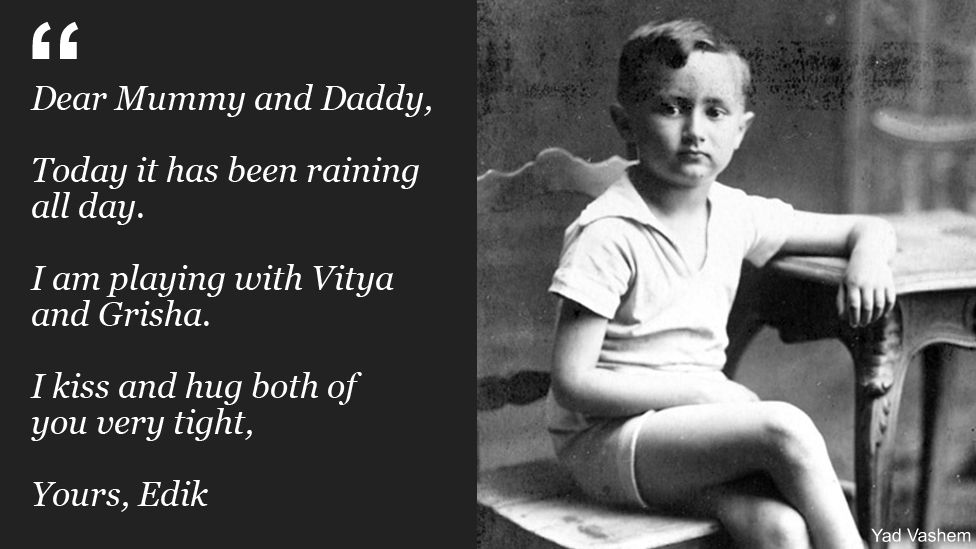

One of the biggest gaps is with children, of whom some 1.5 million were murdered in the Holocaust. Only about half have been identified.

“It’s one of the saddest things,” says Dr Avram. “We have reports where parents are named with say three or four children, unnamed. They were little children and people just don’t remember.”

The aim is to turn them from anonymous statistics into human beings again, like seven-year-old Edward-Edik Tonkonogi, from Satanov in Ukraine. His childish innocence and sweetness of character come across in a letter he wrote in 1941 to his parents who were travelling with a Russian theatre troupe:

Edik was murdered after the Nazis entered the town that same year. His name was later memorialised in a Page of Testimony by a relative.

As time moves on, the task of finding missing names is getting harder in some respects but easier in others. The availability of source material is greater than ever and advances in technology mean it can be a less arduous task to gather information and manipulate the data.

However, the fewer the names left to uncover, the more activity it takes to find them.

The digital age also means there are more tools at researchers’ disposal than ever before. The department searching for names recently took to social media, including Facebook, in a push to reach untapped survivors. The campaign generated many new Pages of Testimony.

“When you’re talking about social media you have the younger generation now understanding that those names are not in our database and trying to find out the information from their family members,” says Sara Berkowitz, manager of the Names Recovery Project.

Image source, Yad Vashem

There is another significant, sometimes life-changing, outcome of the growth of the names database, which has been available online since 2004. It has led to emotional reunions of survivors who had lived their lives not knowing there was anyone else from their family left alive.

Last year two sets of families belonging to two sisters, each of whom thought the other had perished in the Holocaust, were united after a chance discovery through the Pages of Testimony. It transpired the sisters had lived out their lives just 25 minutes away from each other in northern Israel, but passed away without ever being aware.

In 2015 a pair of half-siblings who did not know the other was alive were reunited as a result of searching the database, while in 2006 a brother and sister, one living in Canada and the other in Israel, were reunited 65 years after becoming separated in their hometown in Romania.

The project has also brought to light other, unfortunate findings. Argentinean-born Claudia de Levie, whose parents fled Germany in the 1930s, believed she had lost four or five relatives in the Holocaust. A search of the database to help with her daughter’s homework revealed in fact 180 family members had been killed.

Further research however revealed through a signature on a Page of Testimony the existence of cousins of her husband, living in Hamburg. The families now speak to each other each week on Skype.

Ironically, a chief architect of the Holocaust, Adolf Eichmann, lived as a fugitive in the same neighbourhood as Claudia when she was a child in Argentina, as she would later learn.

The importance of the mission to recover victims’ names received global recognition in 2013 when the United Nations cultural agency, Unesco, included the collection in its Memory of the World register.

The agency lauded it as “unprecedented in human history”, pointing out that the project had given rise to similar efforts in other places of genocide, such as Rwanda and Cambodia.

Despite the millions of names recorded so far, there is still a long way to go if all six million are ever to be recovered, but those behind the project remain determined.

“I personally would like that we do reach that goal, that at least among those who perished there won’t be a person who remains unknown. It’s our moral imperative,” says Sara Berkowitz.

“Until I sit in the office and days will pass by and I won’t have work to do, I’ll know that we’ve more or less raked the universe to try to get to every name and there is no more there.”